A light is a sign. It should be watched, listened to. Don’t

hide it under a bushel.

Throughout our times, and those before, we have been given

many signs. A leveret killed by a fox and its corpse smeared along the path.

The way crows gather in huge black clouds. Owls hawking eagles. All these

auspices we read in the sky and earth. We have learned to look for these signs,

to watch the colour of sunset and the movement – skittish – of early blackbirds.

To count the families of magpies and interpret them. We know how long to season

oak, harden beech, mix nettle and primrose to heal our people. Some say we look

into the seeds of time to see which will grow and which will not. Well, we are

the sign readers. You ignore us at your peril.

With this meticulous looking and listening, I learned to

love every contoured, coloured space of my country.

When I was a young girl, my mother taught me how to read the

signs. The first spring we sat together under the ash; the air was sweet and

soft as cowslips and Queen Anne’s lace made us a bright cushion. She taught me

the repeated call of the song thrush and to learn the difference in its

numbered refrains. She showed me the badger sets – to read their moods from

their discarded hairs, and to hear of things to come in their snuffling; and in

the call of owls, the movement of bats; the way moonlight falls in the secret

places of deer.

One day, when I was a young woman, I plaited blossom in my

hair and danced between the apple trees to wed a sweet boy. That night, before

we bed, I slipped out in the full moonlight and buried a hard, dry pea in the

earth where two paths crossed. I sprinkled spring water over it, whispered; and

listened. A stillness. Then three screams of the owl. The earth rose gently and

shifted, and a shoot broke through. Satisfied, I went back to my lavender

scattered linen and my sweet Hrafn. I was pregnant by the end of the week.

A time I had with that first carrying, as summer passed and

winter thickened. I read omens in my aching breasts and sickness. My hair grew

thick and long while the pain in my swelling hips interrupted my sleep. The

baby growing in me never seemed still. It writhed before rain when I read the

skies to see the rain coming, it flopped over before high winds. One night, I

awoke to a painless dampness; blood streaked the sheets, and I roused my

husband with shrieking afraid we had lost our child. There had been no signs.

My mother was sent for and we three cleaned the linen and washed me amid our

tears. Two hours later, I felt it move again, a vigorous kicking. But our relief

was broken when the neighbours thundered at the door, screaming that a fire had

broken out in the dry lightning storm and the barn was aflame. In the last two

hours it had taken hold and the village lost four new born calves. Hrafn ran

off to help save the rest while my mother and I looked at each other in the

fire’s distant red glow. We read the sign; clear as morning.

That this child would not need to learn how to read them.

* * * *

When my daughter was born, she slithered into the world with

her eyes wide open. Her left eye wandered outwards, unfocused. The right was

sharp and piercing; it fixed me with her first look as I took her to the

breast. We named her Arndis and my mother mopped the child’s skin with fennel

and cinnamon water and blessed her with ashes. All the while, that unfocused

left eye stayed open and rolled. I watched it that night, the second day, and

the third. It never focused. But after watching and reading, I knew; I could

see it; I knew that eye could see beyond the signs I could ever read.

* * * *

When she is five, I take my daughter to the flower meadow. I

teach her the names of flowers, which tree bark heals, the mood of the weather in

a bird’s cry. I teach her in the May morning to read the signs and she forgets

nothing. She looks off into the distance and her wandering eye, blank behind

the black pupil stares away left.

‘Mother,’ she beams at me. ‘Harvest will be rich this year.’

I smile at her childish tones. But I’m proud.

‘You read the signs well, little bird.’

But now she fixes me a serious look and her left eye droops

more. I am suffocated by a sudden heavy gloom.

‘Store it mother,’ she pleads. ‘And next harvest, and the

one after that, and the next. Eke it out. Plait more straw for trading when it

runs low.’

‘What, child?’ I whisper.

‘Famine mother,’ she answers. ‘In four years.’ And she lays

her light curled head on my lap and weeps.

This I could not read. But she could see it.

* * * *

Arndis turned nine with the last of the lambing. And she was

right. That summer was cold and damp, the valley crops were water-logged and

most failed. Harvest time came, and despite our season’s customs to bless the

land and call for plenty, we had little fresh gathered at the thanking

festival. Yet we were thankful. Our people have long trusted their sign

readers, and when I had called for prudence with our surplus, it had been

stored and extra planted in the good years. We would survive. My child was

hailed as our greatest sign reader yet and those who came out of the forest and

down from the foothills in need gave her thanks. We fed them, cared for them in

sickness, and weathered the famine through the hunger months, until the first

shoots of spring cabbage swelled for picking. In May, we drank our ale, gorged

our bellies full for the first time in months and crowned Arndis as the May

queen with flowers. We danced amid the apple blossom to give thanks in the warm

sun that Beltane: famine was over at last.

* * * *

My child grew and we watched her with love and fascination.

We had no more children, but my sisters did, and my daughter led her little

cousins by the hand to the ash tree in the wildflowered meadow to teach them

how to read the signs. She knew her gift, but kept her instructions temperate

and careful. All our people in the valley and the hills and woods loved her;

our sacred light.

One morning, when she was fourteen, she awoke me early with

her face creased in pain. As I rose to comfort her, I saw the skin beneath her

ribs flushed blue with bruising that flowered there. I held her shaking

shoulders as she cried in the grey dawn light.

‘What happened, my dove?’

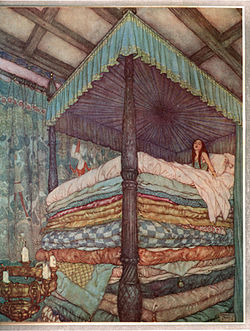

‘There is something in the bed, mother, that hurts me. Like

fingers piercing me, bone-like, evil; I’ve not slept all night but rolled on

bones.’

Of course we searched the bed. We pulled the blankets off to

inspect the sheet. Finding nothing, we lifted the mattress, the bed itself. Still

bewildered, I begged her to lie upon the bed again to try and show us where it

dug the most; and her cries of pain were the wails of a lost child and it broke

my heart so that I ripped the mattress to shreds for hurting her. Despairing,

in a pile of feathers and straw we sat staring at the floor wondering what

could have broken so violently the sleep of my child.

‘Mother, that crack on the ground,’ Arndis started to her

feet. ‘It was never there before. When I kept my corn dolls under the bed for

sweet dreams, it was never there before.’

I dug with my hands. I followed the crease, digging through

the earthen floor. I called to my husband for the spade, we dug together an

appalling hole in the floor of the room while Arndis leaned over, scooping

earth away and pleading that we persevere, it was near, nearer, close now.

Two and a half metres down, my daughter triumphantly pulled

out a shrivelled, mouldering pea.

‘It wasn’t that?’ Hrafn exclaimed in surprise. She looked at

him, tears in her eyes.

‘Damn you, look at her back!’ I roared at him. ‘It did that!

It’s a sign!’

Our child kneeled back on her heels, staring at the pea in

her nightgown lap.

‘What do you see, love?’ Hrafn asked. She looked up at us

again, frightened.

‘Call everyone,’ she murmured. ‘Everyone. It is a sign, and

we can’t prevent this on our own.’

We called our people together in the long barn we used daily

in winter with its central fire and ale store. I had seen my people dance at

Thanking Festival in this hall, and on Wassail, and the Solstice tree clash in

the flickering gold of the fire, vibrating the ceiling beams with their songs.

This morning was tense. The elderly settled nearest the fire, folding their

grandchildren in their laps and others squeezed around them knocking snow off

their boots from their journeys down from the hill homes in a sombre hush. We

sign readers stood at the front, my daughter ahead. My mother, her silver hair

a cloak down her back, spoke first.

‘You know the power of my grandchild.’ She paused to look at

the stern faces ahead that twitched in nods. ‘She has proven it in her birth,

her visions and her warnings. She has kept us safe, ensured our prosperity.’

Murmurs of assent through the fire smoke. ‘She warns us now.’ Here she turned

to my daughter. ‘Speak child. Tell them.’

Arndis stood forward. From behind I could only see her long

hair, darkened to a light brown from its childish gold. Her shoulders were

thin; she was always a small girl. But her back which faced me was firm, her

voice when she spoke, though low, never wavered and I bit my lip to crush the

emotion threatening to dismay me as I looked at her. My child. So young still,

and holding the thick weight of our future in her thin arms that should hold

the flowers and herbs I want to scatter over her beautiful head in blessing.

‘There will be pestilence,’ she said. ‘It is even now

festering in the ground, coursing under the rabbit warrens of our land and

souring the soil. Crops will die, but this is not like our last famine. It will

cause disease in our people, poison our rivers and streams and all, from the

smallest field poppy to the greatest boar in the forest, all will die.’

I watched the faces of our people as the cold, bony fingers

of fear clutched their hearts and stopped their breathing. Silence followed.

‘Can it be stopped?’ a man called from the crowd.

Arndis sought him with her eyes. ‘Yes. It is the war our

King is fighting on his further borderlands. The dead, the starvation and the

rot have infected those lands deep beneath the fields. The blood of injustice

corrupts it all. It is spreading fast. If I can gain an interview with him and

put forth my application for peace, we could arrest the chaos and pour balm on

the land; heal it.’

My mother twisted to her granddaughter, her steel hair

falling over her shoulder. Her voice hissed. ‘You will make this journey?’

‘It’s my duty, grandmother. I must.’

I did not see how my mother swallowed hard, her eyes wild

and her hands before her face. I saw nothing but my own child’s head as I screamed

my protests and clutched those thin shoulders tight to me.

* * * *

I watched my daughter climb into her saddle. She had to jump

a little to make the distance to the stirrup because she is still so young, and

she scrambled and shuffled awkwardly, and I cried then for how will she

convince a king if she can barely reach her own reins? I pinned mistletoe to

her reins for luck, and seeing her cloak was fastened, I stood back, to let her

urge the horse on. My husband urged his on after, his face grim but his heart

soothed to go with his daughter. My own heart was cracking. I saw the fear

through her brave smile and I could not speak, but squeezed her calf muscle as

she moved off. A five-day journey across the mountain pass and down the planes

through the late winter snow.

I was restless all week. I read the winds, the way the

wolves came closer at night, clung with famine. I watched twelve crows descend

in a ring and squawk, fighting over a dead vole. Another snow fall mixed with

the mud stained melt and the paths between our village homes became a stiff

quagmire to snap an ankle on. A grey fog descended, hiding the valley, hiding

the peaks and the trees and hung there for three days. The wolves howled

through. None of these signs were auspicious. The week stretched into another

and a third, then one morning as I went to the wood pile, two magpies bickered

on the nearest branch of the willow row. The sky had cleared and I knew my

daughter was coming home.

Two more days I waited at the meadow edge to look out for

her. At last, as the sun turned the late afternoon sky purple and gold I saw

two figures on horseback. Hitching my skirts under my arm like a wash bundle, I

raced through the muddy snow towards them.

* * * *

It had not gone well. By the fire, with my mother, my pale

daughter told us of her petition. How the king had laughed and put my husband

in chains, and forced him to watch the derision of his child. How the duke had

demanded she prove her power, and took her to a room with seven beds, each

piled with twenty mattresses, and bade her lay down on each one to find the old

pea placed under one of them. How the prince had leered as she lay, stony faced

on each bed. Here she paused. We winced. Hrafn continued that they were lucky

they were not whipped for the king takes not his foreign policy from peasants,

and they were sent away. We stared into the fire silently. We passed the hot

ale around.

‘What now?’ I asked.

‘Blessings,’ my mother suggested. I looked at my daughter as

she nodded slowly, her eyes fixed on the fire.

‘Be frugal with what we take from the land,’ she said. ‘Give

back a morsel of all we take. Then when we have nothing, we’ll have a fat stag

at the door. Be vigilant with our rivers, let not our waste escape in so our

fish are killed. Keep clean. And dance and sing because we’ll need our spirits.

We must love our land and each other to balance the hate of the king.’

* * * *

We watched the deer that rutting.

We left offerings. We blessed the spring when it came, cautiously, and saw the

birth of our lambs, of fallow deer, of pheasants. We lived carefully, with a

new look between each other, of a shared unspoken thing.

And then winter. I watched the

sun swell the thick, blood red of the Ragnarok stories, the poisoned red light

that drives men mad. We drew in our breath, tensed. The earth was the steel

death of winter and it dragged on past Imbolc and on towards Beltane, still

with the low blood sun over short days. We continued our offerings. We tended

the few weak lambs that crept, mewling, into life. There was only brown dead

grass for them to eat in this eternal winter where the green fingers of spring

had failed to stretch out from underground. Would we just die with our land?

And then the falcons began circling high above the mountain and I read the horses

beneath on the mountain pass. They showed me the death might be a different

kind as the king’s soldiers approached our village.

Disease had spread in the city

and Famine clawed at the keep’s walls. The prince had died. The king had

realised the power of my daughter and in his anger and shame, he called us

witches who had cursed his kingdom. He had ordered our capture and the soldiers

had come for us.

The sign readers stepped forward.

We were bound in chains and thrust into the cart that would bear us away. The

light was hidden from our people.

* * * *

A light is a sign. Arndis made a

light. The hardest thing for me was to trust what she saw; trust what I had

never seen. Our arrival to the keep was a humiliation we had never known. The

city’s populace, scabbed with festering sores, stained black and red with

plague had turned out to jeer at the witches. They threw what rotten vegetables

were left in that starving place into my mother’s face and I cringed to see her

strong back sag, her silver hair smeared with filth. Hate is a weapon and they

hated us. And watching them mock my child, and cow my proud mother, I hated

them too. But Arndis leaned forward, trying to clasp hands of the mob and press

remedies in their fists. We have healed plague in our home, and as they threw

cabbages and shit, the shit of their animals at her, she still spoke calmly: yarrow

infusion for the fever and vomiting; garlic and wild thyme against infection. Even

chained to a dungeon pillar later, I felt relief that we were shielded from the

vicious hate that had been whipped up in these people.

We waited there three days. My

mother and we three daughters watched the star and moon patterns through the

small grating that served for a window and tried to balance the good and evil

we saw there. But Arndis looked at nothing, only leaned back against her pillar

and idly fondled the fetters. Then on the third evening, we were visited by the

Duke. When he swept into the room, I watched my daughter flinch and shrink back

into the shadows. The Duke of the bedchamber and one hundred and forty

mattresses to lay my child upon. My mother and sisters and I stepped forwards,

our shoulders a wide wall in front of Arndis as he leered.

My mother lifted her chin.

‘Well?’

‘You will be executed at dawn,’

the duke said, an ugly scorn cutting his nose and mouth.

‘So now you have a notion of the

importance of symbols and offerings?’ my mother laughed bitterly.

The duke leaned in to her, his

face close enough for me to spit at. ‘You will be burned,’ he smiled. ‘That

should cleanse the evil.’

‘And the war?’ asked one of my

sisters. ‘If that continues, burning us will not make a difference.’

‘It will comfort the city and the

king to watch you writhe and die,’ the duke snapped, turning to her. We stood

in our walled line, our faces stone, staring forwards with our chins up and our

shoulders touching. We must not break. My mother inclined her head slightly in

assent.

‘Good luck with it,’ I said. ‘You

know as well as we, that we are all lost. Our deaths will be more painless than

yours.’ I felt my daughter move behind me, my child of sixteen with a life

stolen from her and my rage flickered and flamed. And in my rage, I read what I

saw, and the vision was comforting. ‘You will suffer a death of fire, sir,’ I

cursed. ‘It will consume you as you stand and catch your hair and your fine

robe so you will be a living pillar of flame. Your skin will crisp and crackle

like a Yule hog and your last moments will be anguish and horror. You will fall

to your skinless knees and beg for water to quench it, but your voice will be

lost in choking smoke, and all will flee from you. I curse you, sir.’

He hit me then. But we were a

stone wall and I did not even reel back but was motionless standing masonry. Blood

came from my eyebrow and I smiled. He looked at us in confusion and mounting

horror while he nursed his useless fist, then swept from the room.

That night, we slept little. I

held Arndis to me as my mother clutched her daughters round her. We sang to

spur our defiance and watched the moon, swollen and silver. We wrung love from

the last hours together and tried to rejoice through our strained wakefulness,

that we were together at least. Three generations of sign readers. A pattern. A

sign in itself.

And then the last sign came. Just

as night was almost at odds with morning, a noise from the window roused us. A

magpie had landed there and strutted back and forth in its tailored waistcoat

and frock coat. We watched it, a comforting life in monochrome. Then it was

joined by another. Then another and another. We read aghast, the swelling

visitation until the seventh arrived. It held a piece of sweet-pea in its beak

– the pink and purple of late June. We stared at each other. Arndis spoke.

‘Can’t you see it now mother,

when it is so near?’

I looked at her. Those thin

shoulders, her long hair; her heart that loved so blithely. My heart broke

again. I saw her, our light, and I saw now what the signs said. My mother saw

it, and my sisters and my nieces as we stared, dismayed at Arndis, with the eye

that never met ours, but saw further.

‘When I shout run,’ she

whispered, ‘do not hesitate.’

* * * *

The rest is a series of dark

pictures. We were pulled out at dawn; subjected to more jeering. We cried now

and the king and duke laughed, thinking to have broken our spirits at last. But

the cramping, biting, wrenching loss was not for our own lives, but my child’s,

who knew, all along, what her fate was.

We were bound to stakes and

hefted onto pyres. The man in the black mask with his burning brand stood by,

waiting. My breath caught and my heart fluttered like a wren and the damp on my

hands and under my arms made my bonds slip. The king was speaking but I heard

nothing through the black wall of noise, the black buzz of ‘witches!’ and

cheering as the executioner held up his brand and walked towards my child. Only

a child. And such fear of a child. She twisted her head towards me and smiled,

the most beatific smile I’d ever seen her beam. It was serene, it was joyful,

and it smeared through my tears into something misty and permanent. I could see

her mouth the words ‘now, mother!’ like a triumphant shout, as if she was starting

a race, and the pyre was lit and the faggots caught and a light, a white

shimmering light erupted; burst like a waterfall and fanned out in a summer

heat we had not felt for ten months.

Our bonds singed first, and we

slipped into the kindling. We waded through it, and gathering wrists of sister,

mother and child and ran through the crowd, ran through the gates as soldiers

bolted past us to bring pails to the explosion. We ran out of that cursed place

as it was engulfed in the flaming inferno of my child; burning duke, king and

pauper; melting metal, boiling lead, scorching septic earth and slaughtering

the pestilence, war and corruption that infected the land.

A light is a sign. Her light

could not be hidden.

* * * *

In lands far from ours, a burning cleanses. It opens space

for light, it nurtures the soil; enriches it. The trees grow stronger and the

regrowth is thicker; birds return. My daughter’s fire did this for our land. We

made the journey back through forest and mountain pass, filled half with joy

and half with despair, while the iridescent blue of kingfishers darted past us

in forest streams and magpies called to each other. As we reached the willows

at the edge of our home, we saw the purple and gold of crocuses had broken

through the earth. Spring had come. Our land lived again.

* * * *

I am much older now, but I am a great favourite with my

sisters’ grandchildren. My hair is a steel cloak down my back and my husband’s

is a long white cape. I keep a small shrivelled pea on my hearth to show these

babies and tell them about our greatest sign reader, as I teach them to read

the meaning of magpies, what will come from the colour of sunsets and how to

make a decoction from oak bark. And the light is returned to our people.