I’m sure that pun has been done before. But I have been getting my folk on over the Merrie Month of May and it has raised thoughts and questions that I’m pondering through. Thus I need to write it out and see what you think!

Easter weekend, I danced Morris at the National Folk Festival in Canberra. A five-day folk festival, and incredibly, one that was a fifteen-minute tram ride from me house and had absolutely no mud. Hard for an English girl to get her head round – surely you’re supposed to get up at the crack of dawn and spend four tense hours in the car crawling past Stonehenge on a single track road to get to a festival in time for the first set, and woe betide anyone who forgot their wellies. Mud is such a feature of British festivals that a whole couture has sprung up in designer rubber footwear. So imagine a purpose built festival ground. Not a farmer’s field that gets churned to shit and swamped in so much rubbish that whole eco systems are destroyed annually, but one with logical paths between stages; purpose-built exhibition buildings with stages in them, bars and so much seating. It was so clean!

Unlike me who was dressed in black and sweatily capering about in what they said was 24 degrees but dammit, felt like a hell of a lot more.

So what’s Morris like down under? Well.

I must first say that at the National Folk Festival, Australia mustered up a whole five sides. My Australian Morris friends correct me here – the purpose of the folk festival is to showcase regions, so they specifically invite certain sides from certain states (yeah, and make them largely pay for their own tickets); this year was Big Fella and Little Fella, so (a) side from the enormous state of Western Australia and then Surly Griffen from little ol’ Australian Capital Territory. And of course, the sides from Brisbane, Sidney and Melbourne that won’t be discouraged from any opportunity to get their jig on. So I get that…but after festivals in tiny places like Rochester, Wimborne, Oxford, Swanage with close on a hundred sides with their varied costumes, colours and pageantry, Australia’s festival lacked that immense diversity.

But it did mean everyone knew each other. They all camped together, ate together, drank together and there was a lovely, close family atmosphere. Er, here I must say honestly that it was a family atmosphere if you were in the family; coming in as an outsider to these extremely nice and friendly people was a little harder. I think I personally mistimed me drinking. That early afternoon high of bombing a couple of pints, then the evening dip after pausing. ALWAYS carry on through! But these lovely chaps had grown up together, danced together, known each other for years, and as some of them are separated by the miles of mountains and desert between Melbourne and Brisbane, at festivals they’re very preoccupied with catching up and hanging out. Of course they would be. Ya know, next time will be better.

Now Australian Morris is really into Cotswolds. Hmm. It’s never been me favourite style. And as I often take a sort of ironical approach to any earnestness in Morris dancing, pointedly glazing over when someone starts telling me about villages in Northamptonshire (about which I frankly couldn’t give two shits and it seems particularly ludicrous ten thousand miles away), and I find Cotswolds dancers take themselves very seriously. For a bunch of chaps with bells on. But my my, can the Australians dance it. Watching the likes of Bell Swagger (freakin’ great name) and Black Joak, this must have been what it was like in England in the old days! Vigorous leaping, shouts, strength, grace, my god did it make me want to join in. The old fellas in England would be trembling their bells to hanky-needing climaxes if they had seen it. It’s exactly what they’re talking about as they heavily lean their rotund bellies over my chair in pubs to tell me all about the dance form I’ve been doing for four years.

Or is it? Because these sides have women; tall, strong, beautiful Australian women who add a uniformity to the set by their height and strength and they kick and leap about on light feet better than any man I’ve ever seen in England. Most of the sides were a rough fifty-fifty split and just dispensed with all that nonsense about women not being allowed because Morris here started after Emancipation, instead of before. And it’s a much smaller crowd, so they just include everyone who has the folky interest. And because they all know each other and because they are slaves to the Cotswolds traditions (about which they know far more than me…see above note in parenthesis), they can all join in each other’s dances, which is quite lovely indeed.

So I came away from the folk festival actually wanting to learn hanky dances which was an extraordinary turn up for the books. But only so I could dance them in Australia. But to reflect on it all, there did seem to be an almost crippling self-consciousness in the clinging to the older Cotswolds traditions. I’ve always found that to be the more sanitised side of Morris; the kind that goes to church and won’t necessarily be found in the dark brandishing flaming torches (does one ever do anything else with a flaming torch?), drinking heavily and communing with some kind of more ancient, less definite thing. Where the hell was the border Morris?

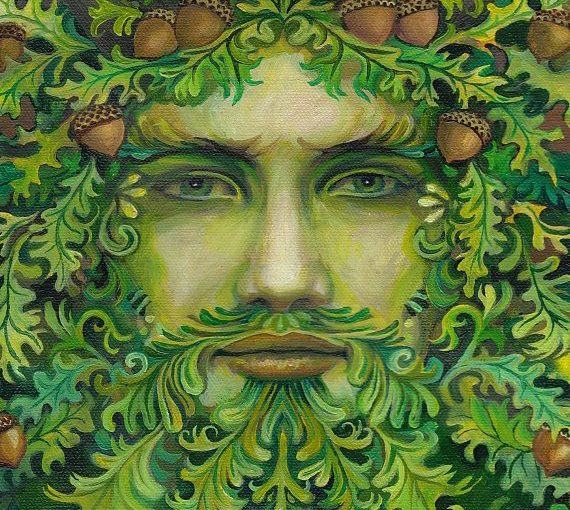

I am assured that Border exists in Australia. When I attend the Huon Valley Midwinter Festival (gleeeee!!) in July, I expect there’ll be a lot more of the burning shit and creepy costumes. Border has always seemed to be the more progressive – even the name suggests it is the pushed aside, marginalised people that have had to forge a space of harmony between things. Well look, that’s my interpretation, and yes, I know about bloody Wales and protecting frontiers. Border sides mostly always have women, do more painting and costume (if it’s about disguising yourself with paint and rags so you can hide not only your face from your employer as you beg for money, why not your gender?) and there is a more pagan, earthy feel to it. It’s also the way Morris is progressing in England; you can be a catch-all for the folkies and the goths and more young people are interested in that style of dance. It’s the style (in England) of the young, and more Border sides are started up that Cotswolds.

Cut to England and I wake up on a narrowboat with the croak of an owl at four in the morning on May the first. Into the blue light in our bells, we step off and I’m drowning in the song of blackbirds and I have forgotten how beautiful they are. Driving towards the beacon at the end of the ancient Icknield way, we encounter a large deer on the lane, then arrive on Pitstone hill amid the yellow glow of a carpet of cowslips and New Moon Morris dance and sing the glowing red ball of light up. I can feel spring.

In Rochester that weekend, a hundred sides in different colours, ribbons and feathers are celebrating the May-o and diversity and colour are the sign of English Morris. Ok, not proper diversity, Morris dancers are still resoundingly white and English, but there is a huge mix of styles and colour. The immense percussive orchestra of the Witchmen boom out across the streets and you find your legs running towards the sound to see what’s going on and you are not disappointed. But my favourite discovery this year was a brand new Morris side called Hugin and Munnin – a pair of dancers and one musician who dress as crows (after the Norse myth of Odin’s ravens, Hugin and Munnin that follow him in battle and fly out around Midgard each morning to bring him news from across the worlds) and did some crazy shit with sticks and shields, and god knows what was going on with the big black bollock balloons that came out and ate people’s heads.

But this is what Morris is about for me. Two people starting up a new side in whatever tradition they fancy, bringing in whatever ancient mythology floats their respective boats, thinking about the spectacle, and incorporating a bit of heavy metal into Morris. Fuck yes dudes, fuck yes. Folk must grow and follow the folk and their culture. Otherwise it fossilises into the elite or the useless.

And Australia seems to have not got there yet. Perhaps it’s still establishing and then when it’s secure, it will move to the next phase. You know, like after the rise of capitalism, there is the inevitable rise of the workers. Yeah, just like that. There are new sides arising in Australia – I had the privilege to witness the birth of one at the Folk Festival. But it was a side of garland dances. Sigh. I can stick a garland dance even less than a hanky dance. But bloody hell, this was amazing! Imagine in May, the frothing of hawthorn over the hedgerows and young, lithe, beautiful girls gather blossoms and weave them into garlands and into their hair and dance. What could be more beautiful? Well, when done by ancient women in a grey town centre, which is the only way I’ve ever seen it done, a hell of a lot could be more beautiful. But in Canberra on that special evening, with fire circles giving light and heat, out stepped an amalgamation of young girls and men from several sides wreathed in green and silver with gold fairy lights in their hats; they danced beautifully and I thought I was on the bankside in a cowslip’s bell where the bee sucks and all the fairies of A Midsummer Night’s Dream were dancing for Titania. It was beautiful.

Australia is reviving Morris and doing it properly. But now it needs to grow. It needs the courage to start something new. Miles Franklin found that her niche as a writer was not regurgitating the castles and grey moors of Europe. It was ‘off her own hook,’ by making something new, embracing her landscape. So Australian Morris; that is your next step.