‘There’s quite a lot of blood on this one,’

Tessa muttered into the steaming sink.

‘What?’

Myrtle looked over, elbowing her damp hair away from her eyes. ‘Another miscarriage?’ The grey haired woman

looked up from the mangle.

‘Bring

it over.’

Tessa

pulled the sopping sheet out of the tub and twisted it fiercely to ring out the

excess water. Holding it away from herself and leaning back, she carried it

over to the mangle.

The

older woman absently drew her finger in a crest behind her ear, clearing away

strands of hair she’d never realised had thinned. She gripped the folds of the

sheet in both hands, holding flat a portion of the stain. Her green eyes

stared, narrowing as she considered it.

‘No,

the stain is too dark and it’s too near the top of the sheet.’ She pulled

another handful of the linen up into view. ‘And here’s the menses, further

down.’ Her eyes locked Tessa’s as she handed the sheet back and they remained

this way for a moment. Myrtle had also stopped and all three women looked at

each other over the blood smeared sheet with set mouths and jaws flinching.

‘Just

clean it,’ the older woman directed.

Tessa

took it back and scrubbed it viciously in the thickening silence. Turning her

face, but not her eyes, she spat over her shoulder. Her mouth grimaced.

‘It’s

nearly every week now you know.’

Myrtle

also looked up again and slapped her brush against the tub’s side. ‘And it’s

just a mindless–’

‘Clean

it.’

Tessa

scrubbed bitterly and the stain began to diminish. As if all the misery and

ugliness in the world could be cleaned away just like a stain on a sheet. With just

a little effort and pain, as her knuckles hit the side of the tub in the fierceness

of her scrubbing. Myrtle’s face also twisted as she wrung sheets until her

hands hurt. Over it all; the faint creaking of the mangle as the older woman

turned the handle. Rotated it rhythmically to impose order on a wrinkled sheet

and a rumpled world; to smooth out and remove her sorrows and those of that

woman upstairs, shivering alone on her tower bed.

All

three minds wandered through different passageways to that same woman. Tessa

thought of the ceremony, Myrtle of the girl’s arrival, drenched from a violent

storm; the older woman the first miscarriage. All thought of the desire in the

Prince’s cruel eyes and the delicacy of the pale girl.

Ripe

for violence.

Myrtle

cleared her throat. ‘It’s been over a year since she came now.’

‘No,’

Tessa corrected, ‘It was just such bad weather that week. She arrived at the

start of August. It’s only spring now.’

‘Oh

yes,’ Myrtle looked up to search for the memory and nodded. ‘August rain can be

as bad as November; the clouds drop and you wouldn’t know the difference.’ Her

eyes glazed again. ‘She was so straight-backed,

wasn’t she? You could tell she was beautiful even though her hair was plastered

to her face and her cloak soaked with mud nearly to the elbow. And she didn’t

cringe in her wet things as she moved, she was…’ Myrtle searched the high

ceiling to her right again for the word. ‘Proud. In the way she walked I mean.’

Tessa grunted her assent.

‘And

she spoke nice. Quietly, but assured. Kind. They should have worked it out from

that.’

‘But

there has to be the Test,’ the old woman spat.

Oh

of course. There must be the Test. Tension bubbling and steaming on the borders

for months, allies desperately yet fruitlessly searched for and always the

anxiety for an heir, an heir. Three years hunting for a suitable alliance while

skirmishes broke out and trade lines were blocked, until the kingdom was all

but cut off and the Queen despairing while her son rode out to find soldiers at

the borders and satisfaction for his lust on the peasant girls the other side.

And this bedraggled woman, claiming to be a Princess from another Kingdom who

only asked for a night’s board with her pledge of great royal future recompense

for the kindness, was promising. She was already at a disadvantage; alone, in

flight, in need. She could be compelled. Then alliance, an heir, stability. But

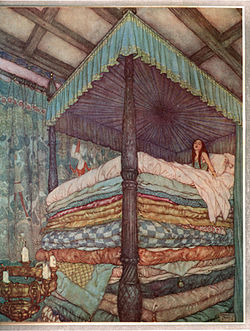

to be sure. So the Queen made assurance double sure and with a painted smile,

led the girl after dinner to her bedchamber heaped with mattresses. Twenty

stacked to the ceiling; the Princess lay there like a fresco painter for the

worst night’s sleep of her life.

‘Just

a little pea under all those mattresses,’ the old woman murmured.

‘Just

a little prick,’ Tessa sneered.

‘Oh

Tess, honestly.’

Tessa

defended her crassness. ‘She looked worse the next morning than the night

before! Haggard. Her eyes were hunted and black. And how she struggled down the

stairs. She’d asked for help the night before. I know it is just a pea, but

they knew what they were doing, how could they hurt someone so defenceless?’

‘Oh

the elite are a cold lot I’d say,’ Myrtle suggested. ‘And it’s a Princess’s

duty to be sensitive, to endure for her Kingdom. I suppose once she’d proven

her worth, she knew they needed her and she owed them, so she had to stay. But

look, when did you see her? I only heard about it from Mary because her Stephen

was serving at breakfast.’

‘Because

I changed the damn bed,’ Tessa retorted. ‘Eliza couldn’t manage it on her own,

there was so much linen. So they sent me up. As I left with me arms full of

bedding, she was still making her way down. Her face was contorted with pain,

she was biting her lip to stop from whimpering. And the Prince was there, with

the Queen, at the bottom of the stairs. Watching intently to see if she had

Passed. He had both hands in his pockets and that little smirk and he watched

her all the way down. Every step. She was obviously in agony and he never said

a word nor moved to help. Nor the

Queen.’

‘Breeding,’

Myrtle sneered. Tessa snorted.

‘Well

you can keep it.’

With

the Test passed the kingdom was saved. The prince took her as his bride and

they had a real princess at last, from a powerful dynasty; a union, an

alliance. They were married three weeks later at the start of September. Every

servant was ordered to wash and turn out to throw the pink and blue flowers.

There was substantial largesse in the celebration. A feast was put on for the

servants too, a fiddler was brought from the next valley, and there was

dancing. Myrtle remembered the fiddler very well.

But

not so well as they all remembered the couple walking out of the palace

courtyard after the ceremony. The Prince in his finery, his black hair curling

just a little above his collar. His overwhelming exotic scent of bergamot

masking the sweat of the warm day as he walked amid the flowered arches through

the double line of his cheering subjects. Hope for the kingdom! His long,

straight nose curled his upper lip as he smiled right and left right over his

bride’s head and the desire was savage in his eyes. It chilled the women as he

passed them. And his bride, squinting in the bright sunlight, looked down, still

obviously suffering; chewing her lip as she controlled her pain in her slow

walk half a pace behind the groom.

Holding her grace, hiding her limp. And spreading upwards from the low

cut of her bodice, staining her pearl white skin; the blue and black blush that

in three weeks, had not faded.

Autumn.

There were subsidies for trade, the economy improved. The women felt it in the price of flour and

fish. More ribbon at market. More pennies to buy it. There were

reinforcements at the border, and a peace of a kind had been sustained through

to winter. Strong and stable. But still

no heir.

That

first infliction, the black flush after the storm-soaked August night, was only

the start. Conceiving the heir was next. Uncharitable gossip ripped through the

servants’ hall about the Princess walking awkwardly, sitting gingerly. Then a

breakthrough, whispers of a pregnancy at the start of Advent. A God given

Christmas gift for the Kingdom! Then at the end of January the washerwomen

found the bright red political disaster smeared all over the bedsheets and a

cloud fell over the palace. The older woman washed that sheet herself, taking

her time reverently, learning every spot and matching it to her memory, never

mixing the splashes from her own eyes with the soap from the tub. Washerwomen;

cleaning to purify the ugliness from the world. Then a storm shook the Kingdom

one night in February. Without was all thunder and the screaming wind, beating

the rain relentlessly against the fortress walls, and within the Prince was beating

the Princess against the walls in his fury. Still no heir, no heir. How could

peace last without one?

Three

servants attended the Princess that night to bathe her skin and press it softly

with witch hazel. But skin is not like the sheets the washerwomen took, and

while blood can be rinsed away, the blue blush cannot. The Prince was subdued

in the days after this and the Princess kept to her chamber. The moon waxed and

then when the washerwomen cleaned the menses off the sheets, blood from a battered

face began appearing regularly.

‘It’s

done,’ Tessa said at last. She threw an end to Myrtle and they began twisting

from both ends to ring out the water.

‘It’s

all we can do,’ the older woman sighed.

‘It’s

like we’re hiding it.’

‘It’s

all we can do.’

‘Can’t

she ask for help?’ Myrtle blurted. ‘Powerful family like hers, I’m sure they’d

not like this happening to one of their line.’

‘I

suppose it’s probably shame,’ the older woman answered.

‘You

had none,’ Tessa reminded.

‘Well,’

the older woman’s eyes darkened. ‘Maybe she has no one to ask. Perhaps it’s

different asking a neighbour as opposed to a far-off Lord who’s married you

off.’

‘Our

little coup de grace was pretty good,

wasn’t it?’ Tessa snickered.

‘Yes…’

the older woman admitted, allowing herself a half smile. ‘After twenty five

years, another day drinking the rent and he never knew what hit him.’

‘Tessa’s

poker did, I recall,’ Myrtle grinned. ‘And off away he went at last! A well-co-ordinated

operation, ladies.’

‘Well,

enough was enough, wasn’t it,’ the older woman leaned back from her waist to

stretch out her shoulders. ‘I make enough from the wash and it’s peaceful

enough indoors now. It’s different for you and your men these days. You can

build something. And your sons will be better. And your daughters will never

have seen that sort of thing.’ She finished her stretch and held out her arms.

‘That’s fine girls, bring it here now. It’s the last one, then we’re done and

tomorrow is Sunday.’

‘You

seeing your fiddler tomorrow Myrtle?’ Tessa asked with a devilish glint.

‘Stop

calling him that, his name’s David.’

‘He’s

good though, isn’t he? At fiddling?’

‘Stop

it. Honestly Tessa, you’ve got no poetry in you. We’ll walk up the crag to the

tarn. He said he’ll bring his violin. You know, when he plays, it’s like being

on the crags with the heather, it’s lovely.’

‘Yep,

soaring up there, penetrating those clouds, all very…’

‘That’s

enough girls, pack it in and go home,’ the older woman interrupted as she

emptied the tubs. The women splashed cold water on their faces to cool

themselves, then dried off their arms and folded the last sheet. Myrtle opened

the door into the bright early May sunshine.

‘How

did your apple wine come out in the end?’ she asked, turning hopefully to the

older woman, who smiled knowingly.

‘Well,

I suppose it needs a test!’ She stretched her arm through Myrtle’s to support

herself and reached for the other girl. ‘You too Tess, come round to mine first

and try it. If it’s any good, I’ll pack you both off with a jug. I’m sure you’d

like some for your little outing tomorrow Myrtle, in case of a picnic, and

Tess, I’m sure you and your husband aren’t averse to a weekend tipple.’

The

women walked home in the sunshine.