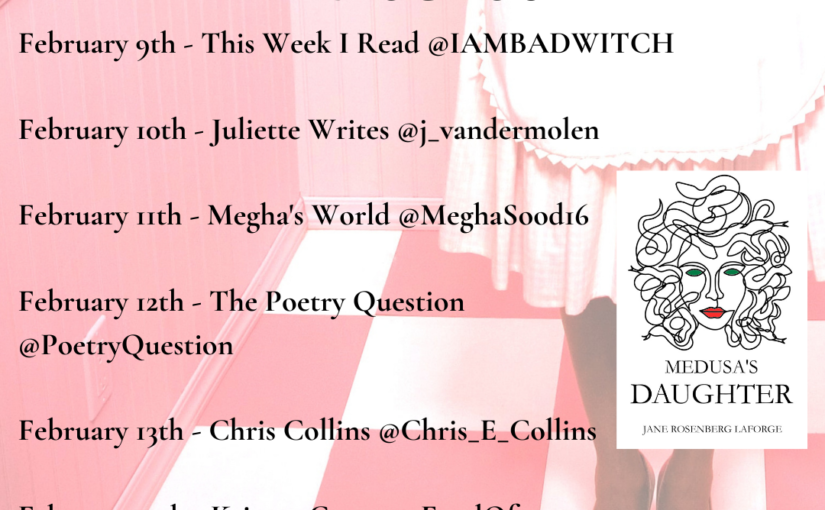

Jane Rosenberg LaForge’s most recent poetry collection Medusa’s Daughter really got me thinking. Like any conscientious reader, before settling down to gorge myself monstrously on a three-day poetry frenzy, I went through my classics. Checked the original. Then had a wider look about on account of the H.A. Guerber collection presenting a particularly sanitised version of the myth.

What unveiled itself ultimately is that this collection not only draws on the Medusa myth to interpret and make sense of self; identity and a relationship; it also threw light on the Medusa myth itself. When we meet Medusa in the Perseus myth; she is a hideous, serpent-haired Gorgon so ugly that her gaze turns you to stone. She is finally vanquished and turned to stone herself when exposed to her own reflection in Perseus’ Goddess gifted shield. Not so with LaForge’s Medusa, whose impact is never extinguished or rendered harmless. Instead, she is made real, explained, even forgiven, and she forces the reader to confront not only Medusa’s origins; her rape by Poseidon and senseless punishment by an offended Athena, but also that all monsters have origins; have loss, potential, beauty and virtues; and all people have monsters.

The voice of the poems is the daughter of a Medusa mother. Initially confronting, the relationship is not warm: no insipid admiration could create such an enduring and powerful illustration. LaForge introduces her key motif of stone, early. Seizing the Medusa myth’s curse of petrifying others, she identifies her Medusa with this image. She speaks of ‘hard black anthracite’ in the opening poem ‘Medusa’s Resources,’ and alludes to this frequently, drawing in other minerals, ‘granite’ and bricks. In ‘Medusa’s Speech’ the image is developed. Stone connotes both strength and resilience, but also rigidity and coldness. Both are apt metaphors for LaForge’s Medusa and her trauma. The reader is told ‘You’d have to split stone … shave granite/ Or pyrite to reach the history/ That cannot speak for itself./ She would have buried it in concrete.’ Stone is associated with the collection’s recurring theme of repression; burying painful memories that the speaker attempts to mine to better understand the woman who is gradually revealed as a German Jewish refugee. LaForge portrays her as sealed in habits and character; in the poem ‘Animus’ she is ‘rigid to the point/ of breaking like flint, on the edge/ of self-immolation.’ The image is negative, this Medusa mother was ‘Cold of heart, blood, chilled in respiration.’ ‘Medusa in Suburbia II’ ends with the devastating lines, well emphasised with enjambment and stanza spacing; ‘Ask her if she still loves, and whom./ Her children are waiting.’ The damage done by a stone mother is the enduring Medusa curse.

Curses thread through the collection. Medusa’s metaphorical curse hovers over the physical curse of War, the trauma of ‘blackening of names/ through long knives.’ References to the ‘Third Reich,’ Japan and ‘abuse of the smallest molecules’ evoke the Hiroshima bombings and the lasting effects of post-traumatic stress and harmful radiation. Disease and madness blight the lives of the poet’s subjects, the ‘mean reds,’ the ‘manias, blackened like maps’ eating up and wasting time, botching abortions, and failing suicides reducing the Medusa to Ruins, ‘her hands rheumatic/ and her womb cancerous.’ The imagery of tumours is shown to corrupt the body of Medusa and also her children, with the premature death of one and the failing kidneys of the other. But coldness is also a curse; Medusa’s victims were turned to stone. The poet explores this while she struggles with how to provide a warmer childhood for her own daughter in the three ‘Nursing’ poems, struggling with guilt and anxiety about being enough for the third generation.

The poem ‘Pygmalion’ further manipulates the classical myth, subverting the story of a beautiful statue becoming human. For LaForge it is the statue; the mother, that corrodes and weathers. LaForge does not romanticise; she presents this mother as hideous. The poem ‘When Medusa Was Beautiful’ describes her hair ‘greyed/ into snakes,’ her lips ‘thinned into a pursed expression;’ an obese woman with no ‘teeth and eyelashes.’ But the Pygmalion reference alludes to Transformation, and further sculpture imagery, references to sand and glass, and how Medusa creates in ‘Medusa the Mason’ and ‘Medusa’s Men,’ show her potential and power. The poem ‘Stones’ alludes to the ore that later becomes gems, the poem ‘Animus’ talks of ‘smelting fire.’ The speaker knows this Medusa can pressurize stone into something beautiful, could be something incredible.

Because ultimately, LaForge’s Medusa is impressive. Despite her trauma, the oppressions of society and the patriarchy, Medusa won’t conform. Her very monstrous ugliness is a rebellion, ‘Gray among the bottled/ blondes, numbers seven through eleven.’ She is real among the robotic superficiality and cruelty of suburban bullies. In the poem ‘Jungle Red,’ LaForge celebrates her mother’s violent red lipstick, her challenge ‘for speaking when your presence/ should have been of a single/ dimension,’ while also lamenting the things her mother could have been if born in another time or place. ‘Medusa the Mason’ considers ‘what might have blossomed if she were/ given protractors and slide rules,’ and ‘an enterprise/ to run like the one she ran for our father.’ It is clear to the speaker that her mother was clever and was not fulfilled in a world that treats women as gift horses, as suggested in ‘Horses.’ The poet finally attains resolution in ‘A Year’s Time,’ the poems having worked through memories of trauma, sadness and neglect to the ultimate admission of acceptance: ‘I’m not ready/ to let you go./ Not yet.’

It would have been a poignant place to end the collection. But LaForge defies convention and chooses to finish with ‘Medusa’s Grandbaby,’ a poem about her own child and the imagery of ‘vessels,’ ‘blood,’ ‘molecules,’ even ‘hospital’ shows the continuation. This child can take the myth and make of it something different, perhaps take something that is not cold stone, but its manipulator, the Pygmalion Mason and make something new out of those same materials. In poems like ‘Medusa in the Mirror,’ LaForge takes the curse, the stone in her, and chisels at it, forces herself to look and understand, and then create the new thing her mother could not. She sees herself in the ‘feldspar,’ the ‘lithium,’ and with the smelting imagery, has potential to change. Like Garbati’s statue of Medusa, here is the woman behind the monster, interrogating her curses, and making them new for them to be worked on and resolved, by the next generation.

As ever, apologies to the poet if I’ve totally missed the mark with my interpretations and that was ‘not it, not it, at all.’ But I loved this collection.